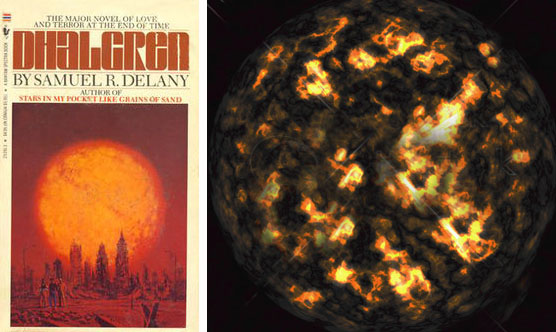

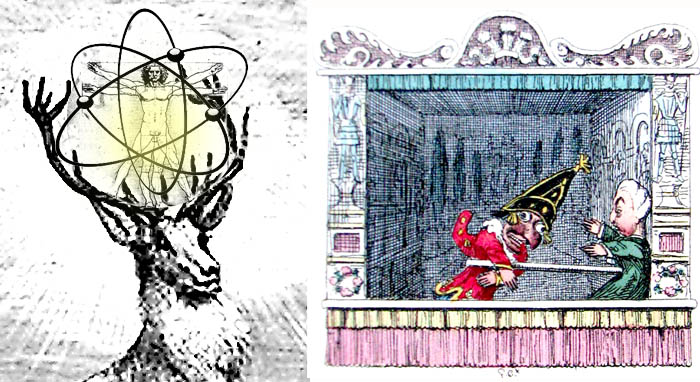

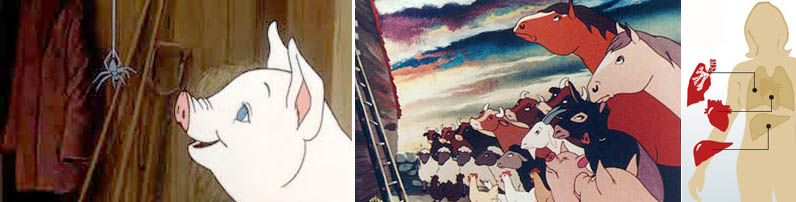

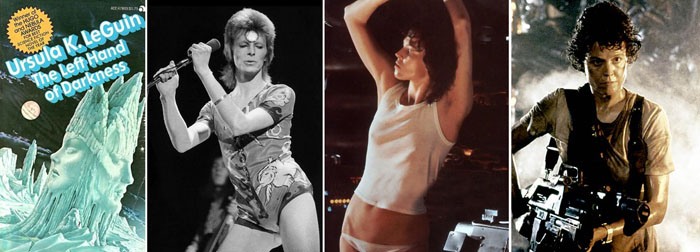

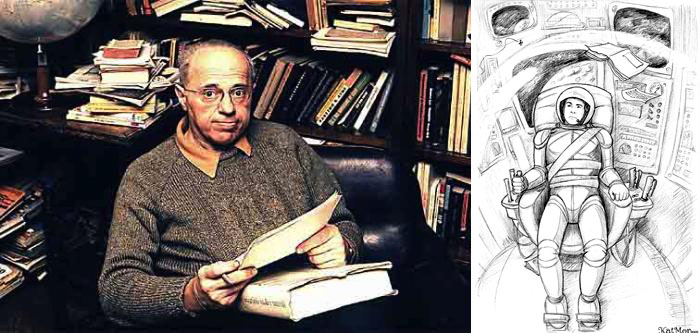

| Top ten science fiction/speculative fiction novels Sally McKay was reading and/or pondering this year, with various tangentially related images for illustration. 1. Year of the Flood, by Margaret Atwood  I picked these scenes from 28 Days Later to illustrate Margaret Atwood's Year of the Flood because there are some real similarities, both in plot and atmosphere. In Atwood's book it's the near future and due to a technoscience catastrophe in genetic manipulation humans are pretty much done for while everything else organic, including weird new species, has started taking over. There are scary, macho, militaristic dudes with knives and guns and tough survivalist women who figure out how to deal with them. The main characters belong to a religious cult based on environmentalism and science. In their incantations they rhyme off their Saints, including Saint James Lovelock, Saint Stephen Jay Gould of the Jurassic Shales, Saint E.O. Wilson of Hymenoptera, and Saint Dian Fossey, Martyr. Oh, and Saint Jesus of Nazareth, Fish Conservationist. Atwood is really riffing in this book, and in parts the fast-paced complexity of cultural-referencing starts to feel almost like William Gibson or maybe more like Douglas Coupland. Anyhow, it rocks, and it's way more fun that some of her other dystopias, like Handmaid's Tale. Year of the Flood is an excellent sequel to Oryx and Crake (which I also loved) but it totally stands up on its own. 2. Dhalgren, by Sam Delaney  Urban sex and violence and the end of the world. Delaney writes great characters and sets them in a situation that is never really explained. Everything is fucked up. The sun is fucked up and the world seems to be ending. People are banding together in tribes and cliques in the streets of a big city (New York). Squatting, fighting, foraging, partying. The main character is queer and charismatic, one of those unwilling leaders who is forced to learn how to wield his power. It's a door stop, and a page-turner. I thought about using Escape from New York as an illustration because there's, you know, hedonism, punks and street gangs and fires-in-a-barrel. But there's an existential streak in Dhalgren that keeps it more interesting than just a porny paperback, and the book's cover, with all it's sci-fi cheese, is perfect. I also picked a stock photo of a dying sun. 3. Enchantress from the Stars, by Sylvia Louise Engdahl  I really ought to read this one again. It's been about 35 years. Here's what I remember — People from a technologically advanced sciencey planet show up on a peasant-type planet that has been taken over by a bunch of resource-extracting developer-types from a business-oriented planet. The advanced technology people are there to intervene and help the peasant people but they have a Star Trek-style prime directive thingy so they can't let the peasants in on any of their science secrets. The developer people have bulldozers plowing down villages and forests and the peasant people think the machines are monsters. The techno people pretend they are sorcerers and enchantresses so they can use their science weapons on the bad guys. Oh, and they have telepathic powers, which they have to hide. But it turns out that some (well, one) of the peasant people have telepathic powers too. Of course there's a transgressive peasant/techno BFF/love affair (written for 12 year olds). There's a frigging great scene where the main telepathic technology "enchantress" gives the main telepathic peasant character a wadded up bit of bread and tells him/her (can't remember the gender) that it's a magic pill that will block out pain because the peasant person is about to get captured by the baddies for some kind of torture. The peasant person is really smart and figures out that the so-called enchantress is messing with his/her head... stupid fake bread pill, not magic at all, etc. But the enchantress person breaks the prime directive, and, through the awesome power of telepathy, manages to communicate with the prisoner in his/her cell, and lets him/her know that yes, the bread pill is a fake but he/she has the power within himself/herself to detach from the pain and withstand the upcoming torture. Crazy! And It works! In the end, this being a kids' book, the smarty pants magic/techno people and the peasant people manage to drive the developer people away and then the techno people also leave so the peasant people can get back to their normal lives. But it's very sad because the main peasant character has had a taste of advanced science/telepathy/magic/technology but now has to stay behind in the muck to be a leader for future generations (at least, that's how I remember it, it's been a loooong time). 4. Neuromancer, by William Gibson  Who do you like better, William Gibson or Neal Stephenson? Stephenson can do character development and create a compelling narrative, but Gibson broke the seal on cyberpunk with his ruthless, hard-edged postmodern use of language. Gibson was a master of the plausible near-future and Neuromancer introduced readers to a world that was awful, familiar, prescient and also kind of fun. I chose Existenz as an illustration because the visceral, spine-crunching depictions of jacking-in evoke the kind of painful reality-wrenching that Gibson's characters undergo when they shift in and out of the matrix (way better than the smoothed off edges of The Matrix movies). I chose Blade Runner because, well it's just the best cyberpunk movie ever. Von Bark tells a tale of Gibson going to see Blade Runner right before Neuromancer came out and falling into a pit of despair because he felt like he'd been scooped. I chose Grace Jones because that's who I'd cast to play Molly. 5. Ridley Walker by Russell Hoban  Originally I was going to leave this one off because others seemed to be more in the forefront of my mind, but while working on this list I realised that some small part of my brain has been permanently assigned the task of thinking about Ridley Walker all day, every day. The book takes place in an invented language and you just have to keep reading until you get into the groove and start to understand it. It's a post-nuclear-disaster, medieval-style, pagan-ish society on the brink of re-discovering some get-us-out-of-the-dark-ages technology. Their creation myth is great, enacted in the form of a punch and judy style traveling puppet show. In the hart of the wood there's a little shining man, named Addom, who get's split in two. The hart of the wood is both a big stag, with a little dude hanging out between his antlers, and the heart of a tree, which provides fire. Some hero named Eusa did the whole Addom-splitting thing. Here's an eerie snippet from the post-apocalyptic lore. Owt uv thay 2 peaces uv the Little Shynin Man the Addom thayr cum shyningnes in spredin circels. Wivverin & wayverin & humin with a hy soun. Lytin up the dark wud. Eusa seen the Little 1 goin roun & round insyd the Big 1 & the Big 1 humin roun inside the Littl 1. He seen thay Master Chaynjis uv the 1 Big 1. Qwik then he riten down thay Nos. uv them.I collaged my own illustration of the little shining man riding the stag (Hoban himself was in part inspired by the story of St. Eustace who allegedly came across a stag with a little shining crucifix. I don't know how Eustace relates to Hubertus, but this is where I got my stag.). Of course there's also the whole Jabberwocky/crawling in the muck/medieval peasant thing going on too...with Punch n' Judy to make life bearable. 6. Never Let Me Go, by Kasuo Ishiguro   I loved this book so much that I can't bring myself to see the movie. Ishiguro is probably best known for Remains of the Day. There's a similarity, in that the characters are contending with unthinkable horrors by shifting between states of denial and resignation. Life goes on. Augh! It's horrible. I chose Charlotte's Web as an illustration because as I child I was utterly creeped out by the idea that humans could slaughter a talking pig and I was traumatized by the pathos of a spider and pig bonding out of necessity under such dire, tragic conditions. Never Let Me Go inspires the same feelings in me (except now I am a grown-up and the characters are human). And Animal Farm...well...it's just more of the moreness, only it's about how individual critters internalize state oppression so that the situation becomes self-perpetuating. OOf. It's all too nasty, but Ishiguro is such a good writer that the misery is somehow mitigated and everything that happens feels like it's bathed in a clear and watery light. That's why I chose the sanitorium. 7. The Left Hand of Darkness, by Ursula K. Le Guin  I read this book several times when I was a kid because it just seemed so sensible compared to everything else out there. People can be androgynous — D-uh! There's some setting and plot and stuff like that but I forget it. The cover is a classic and the other images...well, let's just say that science fiction does gender-bending really, really well sometimes. 8. Fiasco, by Stanislav Lem  I restricted myself to one book by Lem because otherwise everything on this list would be by him. I don't want to write spoilers for Fiasco. I will say that the story lives up to the title. Lem is really really good at metalevels of thought and meaning. His plots are often quite unhinged, and, pre-cyberpunk, his characters slip in and out of various sorts of reality. But, you know, it's human astronauts in space dealing with time, technology, and the possibility of life of other planets. Sounds like classic sci-fi and it is - Lem's powers of description are great and the stories are gripping. His combination of philosophy & boys home adventure makes for rip-roaring tales with really awesome mind-bending twists. In Fiasco the world remains pretty consistent, but the story is a tangle of tangents, all of them page-turners, and everything classically structured to return the reader to the urgent, over-riding narrative. I chose this picture of Lem himself because you can see in his face how much fun he's having and that mischievous teasing is there in the prose as well (and comes through great in translation). Plus a really great fan drawing of Lem's recurring character, Pirx the Pilot. 9. Anathem, by Neal Stephenson  As implied above, back in the 90s Neal Stephenson gave William Gibson a bit of a run for his money in the cyberpunk genre. Stephenson's narratives were a little tighter and his characters a little less adolescent, but Gibson always had the edge with his fantastic lingo. Eventually Stephenson stopped writing straight-up sci-fi and moved into historical fiction about science and technology. Anathem is a return to the classic sci-fi arena, and this time it's all about language. It's as if Stephenson decided to take one more crack at Gibson, this time on Gibson's terms.* Anathem is full of made-up words, complete with etymological footnotes and dictionary definitions. At first I thought it was too clunky and forced. But after a while the cultural history of the fictional language just seemed to seep in and take on a deep, rich texture. I chose a big old monastery as an illustration because the book takes place in a setting much like this and — small spoiler — outer space is outer space. It's kind of like A Canticle for Leibowitz, only the story just charges along. Another door stop page-turner. Perfect for staying in bed or travelling. *I'm not totally fabricating this rivalry. Read this, it's hilarious. 10. Mocking Bird, by Walter Tevis  Are people getting stupider? I read this book right after watching Idiocracy. Mockingbird is better — mournful, heart-wrenching, nuanced. Yup, it's the future and everyone has become really, really stupid...and it's up to a couple of autodidacts to save the day. Autodidacts are the tribe I want to belong to, because while our puttering, quixotic information-seeking processes can seem rudderless at times, it's people who gain their knowledge through enthusiasm that really know how to spread it around. Mockingbird was published in 1980 but it keys right into 21st century anxieties.* There's a sad sad intelligent cyborg who just wants to die (but can't), an empathetic thought bus, and a couple of canny humans who teach themselves how to read and get a grasp on history. And a cat. I chose Miyazaki's cat bus as an illustration because of the obvious thought bus/cat bus connection, but also because the tensions of darkness and light in My Neighbour Totoro are laced with a similarly melancholic sense of hope. I picked the image from Man on a Wire beause it relates directly to the plot, but also for it's greyed-out, atmospheric, existential clarity which is the kind of feeling that permeates the book. *I don't believe for one second that people are getting stupider. But there's a polarized battle front emerging with we-don't-read-books-and-we're-proud-of-it types on one side and snobby-elitist-academic-ivory-tower types on the other. yike. As an auto-didact, I feel like I'm being forced to take sides and I don't like it. |

return to: sally mckay and lorna mills

"...allymckay/?53155 Set-Cookie: datr=f2oTTafF2CmgPavCmqDzJda5; expires=Sat, 22-Dec-2012 15:27:59 GMT; path=/; domain=.facebook.com; httponly Set-Cookie: lsd=Xk6Ce; path=/; domain=.facebook.com Content-Type: text/html; charset=utf-8 Connection: close..."

"...allymckay/?53155 Set-Cookie: datr=LnETTfhyrNCMry2FXqaXBgtv; expires=Sat, 22-Dec-2012 15:56:30 GMT; path=/; domain=.facebook.com; httponly Set-Cookie: lsd=npoeW; path=/; domain=.facebook.com Content-Type: text/html; charset=utf-8 Connection: close..."

"...allymckay/?53155 Set-Cookie: datr=UHETTRSxPkx2ttZm5zvGMnCb; expires=Sat, 22-Dec-2012 15:57:04 GMT; path=/; domain=.facebook.com; httponly Set-Cookie: lsd=JCh7o; path=/; domain=.facebook.com Content-Type: text/html; charset=utf-8 Connection: close..."

"...allymckay/?53155 Set-Cookie: datr=SnQTTf3RuxVnPVT4Xo-SRDth; expires=Sat, 22-Dec-2012 16:09:46 GMT; path=/; domain=.facebook.com; httponly Set-Cookie: lsd=Kvn8y; path=/; domain=.facebook.com Content-Type: text/html; charset=utf-8 Connection: close..."

"...allymckay/?53155 Set-Cookie: datr=GHYTTRSzEqa_WNH0ThJHHwcz; expires=Sat, 22-Dec-2012 16:17:28 GMT; path=/; domain=.facebook.com; httponly Set-Cookie: lsd=NDh_Q; path=/; domain=.facebook.com Content-Type: text/html; charset=utf-8 Connection: close..."

"...allymckay/?53155 X-FB-Server: 10.42.219.41 Set-Cookie: datr=iX4TTU5ulmN4dXKQhBiFVqbk; expires=Sat, 22-Dec-2012 16:53:29 GMT; path=/; domain=.facebook.com; httponly Set-Cookie: lsd=-ei9j; path=/; domain=.facebook.com Content-Type: text/html; chars..."

"...allymckay/?53155 X-FB-Server: 10.42.75.47 Set-Cookie: datr=eH8TTcclUp3c8QsY6gPvWE66; expires=Sat, 22-Dec-2012 16:57:28 GMT; path=/; domain=.facebook.com; httponly Set-Cookie: lsd=LX9RP; path=/; domain=.facebook.com Content-Type: text/html; charse..."

"...allymckay/?53155 X-FB-Server: 10.42.129.49 Set-Cookie: datr=JIkTTWKsoy8lUMGTy8AwawWm; expires=Sat, 22-Dec-2012 17:38:44 GMT; path=/; domain=.facebook.com; httponly Set-Cookie: lsd=2RRF7; path=/; domain=.facebook.com Content-Type: text/html; chars..."

"...allymckay/?53155 X-FB-Server: 10.42.96.71 Set-Cookie: datr=_I4TTRTw6p_0bBrJHxU_ad2z; expires=Sat, 22-Dec-2012 18:03:40 GMT; path=/; domain=.facebook.com; httponly Set-Cookie: lsd=BVzAC; path=/; domain=.facebook.com Content-Type: text/html; charse..."

"...allymckay/?53155 X-FB-Server: 10.52.16.49 Set-Cookie: datr=8pUTTSYt614yrxFqwIdf-Pp-; expires=Sat, 22-Dec-2012 18:33:22 GMT; path=/; domain=.facebook.com; httponly Set-Cookie: lsd=vSt8Z; path=/; domain=.facebook.com Content-Type: text/html; charse..."

"...allymckay/?53155 X-FB-Server: 10.52.46.73 Set-Cookie: datr=9acTTTw9QSra5BrfCWiOtzqD; expires=Sat, 22-Dec-2012 19:50:13 GMT; path=/; domain=.facebook.com; httponly Set-Cookie: lsd=uUTBl; path=/; domain=.facebook.com Content-Type: text/html; charse..."

"...allymckay/?53155 X-FB-Server: 10.136.205.106 Set-Cookie: datr=lLUTTWeussHpt19KkmQrlBkj; expires=Sat, 22-Dec-2012 20:48:20 GMT; path=/; domain=.facebook.com; httponly Set-Cookie: lsd=rlAxf; path=/; domain=.facebook.com Content-Type: text/html; cha..."

"...allymckay/?53155 X-FB-Server: 10.43.146.81 Set-Cookie: datr=4QEUTbHorZqw162WgMROGv03; expires=Sun, 23-Dec-2012 02:13:53 GMT; path=/; domain=.facebook.com; httponly Set-Cookie: lsd=wZAYy; path=/; domain=.facebook.com Content-Type: text/html; chars..."

"...allymckay/?53155 Set-Cookie: datr=yRoUTWPY_rR3wAWMLIV8aavs; expires=Sun, 23-Dec-2012 04:00:09 GMT; path=/; domain=.facebook.com; httponly Set-Cookie: lsd=Y_EgM; path=/; domain=.facebook.com Content-Type: text/html; charset=utf-8 Connection: close..."

"...allymckay/?53155 Set-Cookie: datr=lzQUTYS5wn9v_jDSePWOuCzu; expires=Sun, 23-Dec-2012 05:50:15 GMT; path=/; domain=.facebook.com; httponly Set-Cookie: lsd=cHMIv; path=/; domain=.facebook.com Content-Type: text/html; charset=utf-8 Connection: close..."

"...allymckay/?53155 Set-Cookie: datr=fsYUTW3iVCmkhL5mUhBlmO5K; expires=Sun, 23-Dec-2012 16:12:46 GMT; path=/; domain=.facebook.com; httponly Set-Cookie: lsd=qZ-wf; path=/; domain=.facebook.com Content-Type: text/html; charset=utf-8 Connection: close..."