View current page

...more recent posts

Below: David Bowie, Jennifer Connelly, and "Toby" in Escherland (Labyrinth, 1986). As a teenager, A Beautiful Mind Academy Award winner Connelly played the most appealing Everygirl imaginable. Much of what Jim Henson did to her implicitly in Labyrinth Dario Argento did explicitly the preceding year, in Phenomena (released stateside, heavily cut, as the horror film Creepers). In Argento's movie she is poisoned, thrown into a dungeon, immersed in a pool of maggots, and witnesses unspeakable slashings and beheadings and still emerges victorious. What was it about this wholesome, fresh-faced, straight-ahead actress that made directors want to put her in peril? That question doesn't really merit an answer, I just find it weird that Argento's film is the evil twin of Henson's and they both star Jennifer Connelly.

Speaking of A Beautiful Mind, I highly recommend this review by Ted G, who took an MIT class from Nash after the ailing prof was first released from the psychiatric hospital, and whose grasp of the math is better than Ron Howard's.

"Ludo," movements and voice by Ron Mueck (Labyrinth, 1986). Although included in the London-based "Sensation" show as a YBA, Mueck is neither young (he's 44 now), British (he's Australian) or, shoot me for saying this, an artist. Thanks to ad man/collector Charles Saatchi's money and influence, he successfully crossed over from Jim Henson puppeteer to a museum career without significantly changing his schtick--a kind of sentimental high craft. In 1939 Clement Greenberg attempted to nail down what made artists different from illustrators and came up with a dichotomy he called "cause vs effect." Picasso's art made viewers question how the picture was working on them or even what art was (cause) while the Russian neoclassicist Repin painted pictures that told you in every detail exactly how to react to them (effect). For Repin, substitute Mueck's Duane Hanson-style realistic sculptures, which are even less ambiguous than Hanson's because they're deliberately stagy and "spooky." The art world should be more wised up by now. Below: Boy, 2001 (exhibited in the Venice Biennale and elsewhere).

More on the house track "House of God" and R&S Records, the label where it first appeared:

R&S is a Belgian imprint and it's obvious why they liked "House of God," because it's a dark and pounding track (for all the fun--more below) and Belgian techno tends/tended to be over on the industrial side of the aisle. DHS is from Chicago but I know nothing about that outfit. I see "House" as a refinement & updating of "Welcome to Paradise V 1.0" by Front 242, an actual Belgian band frequently described as "techno/industrial crossover" or "electronic body music." It's amazing what happened to electronic music between 1988 and 1991, as exemplified by these two tracks: an astonishing quantum leap in equipment, philosophy, or both. "Welcome" features samples from a Jimmy Swaggart-style televangelist over the metallic "drum machine" sound that everyone was using in 1988, not sure what brand, which now seems brittle and jarring and dated. Also wailing psychedelic guitar samples. The televangelist's words included such club-friendly ironic soundbites as "No sex until marriage!" but also scrambled nonsense phrases like "Hey, Poor, You Don't Have to be Jesus." (An even earlier precedent is Negativland's "Christianity is Stupid" which hacks up a southern sermon.)

"House of God" samples a black radio preacher, from Chicago I'm guessing, who is trying to raise contributions of "50 dollars or more" to build a church called "The House of God." Phrases from his pitch--"I am excited", "50 Dollars or more"--are cut up, stripped of context, and sprinkled throughout the track, or used as rhythmic elements in themselves. The underlying music is minimal, just a thumping beat (an 808?), synthetic cymbals, and a sonar-like pulse--with the occasional hammer-hitting-a-railroad-spike percussion that I'm sure attracted the Belgians. The production is silky smooth, seductive, hypnotic. DHS emphasized the connection between the word "House"--frequently spoken aloud in house music--and "House of God," thus secularizing a concept already corrupted by the phony preacher (and he does sound like a shyster)--or maybe recuperating it? There's a kind of liberating sacrilege in the track's repeated use of the word "God": at one point a sample of the preacher saying "God's House" alternates over and over again with a little girl saying "God" (God's House--"God"--God's House--"God") which almost sounds like cursing and makes me think someone in DHS had a bad religious upbringing. But it also recalls the joyous call-and response you hear in gospel services. It's a brilliant piece of music in the way it tugs you this way and that.

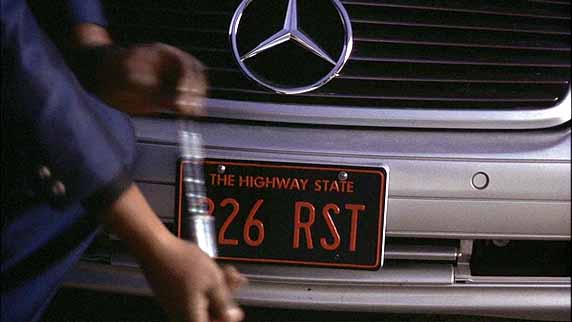

DVD captures from Jim Jarmusch's Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai (1999). In the top frame Ghost Dog removes a license plate from a car he has just stolen and in the bottom, replaces it with a plate from some unsuspecting picnickers. I saw the movie twice before noticing the deadpan mottos for nonexistent states. The music is by Wu-Tang Clan guiding light The RZA, who is featured in cameo (and camo) near the end of the film as a fellow urban samurai. The RZA, who also did the Kill Bill score, is the subject of a wild interview over at the Onion AV Club. Amazing that music so heavenly could come from such a down-and-dirty talker.

(O: What was ODB like before the Wu-Tang Clan? RZA: He was similar, without the money and without the name. I've been involved in a lot of things in my life, and I'd always count him in. Like if I wanted to see some girls, I'd call him and say, "Yo, I've got these girls. These girls are going to steal some shit for us, and all we have to do is hang out with them, spit right with 'em, fuck 'em, and then they'll do that for us." He'd come over, and then the next day, the girls would be ready, and he'd do something to fuck up the whole shit, or get the dough and spend it in one day, or something that's real fucked-up. Like if he got hold of a car, he'd crash it. He was always like that.)

The Ghost Dog score is a strangely heart-tugging melange of hiphop beats, Asian temple chimes, industrial ka-chings & whirs and wispy, pretty recurring melodies. According to the DVD notes, RZA assigned the film's characters their own musical motifs a la Peter and the Wolf. Well, I'm damned if I find any relationship, but each motif is heard exactly when it's needed. The music, working in tandem with Jarmusch's entranced views of the city and frequent close-ups of Forrest Whitaker's sad face, creates an elegiac mood so powerful that it survives even the director's characteristic outbreaks of weird humor and inexplicable behavior (e.g., the old mafia guy suddenly yelling "passenger pigeon! passenger pigeon's been extinct since 1914!"). To hear the score properly you need to get the DVD, because the CD soundtrack is mostly songs by other artists, apparently (or get the Japanese version of the soundtrack for $44).