View current page

...more recent posts

The New York Times ran two articles on Takashi Murakami this week, Roberta Smith's review of the show he organized at the Japan Society, which I quibbled about here and here, and a magazine profile by Arthur Lubow, which I've only skimmed. The musician Momus writes about the latter piece on his weblog, from the angle that he's glad the Times has discovered post-Modernity and recognizes that the Japanese have long been living what the West mostly theorizes about. That is an interesting thing about them--especially the degree to which their popular culture explores the post-human melding of people and machines in the tropes of the cyborg, the giant robot, artificial environments, etc.

Still, do we need the extra loop of pop culture --> Murakami's traveling museum road show --> NY art dealers --> NY Times --> pop culture or do these ideas disseminate to the West just fine through your local video and comic book stores? In other words, if the Japanese have no "high-low" distinction (as these articles are saying) and if Murakami's art and Japanese pop culture are one and the same, why do we need Murakami making this culture available at a higher price level? I maintain his main function is to make Western curators feel better about themselves that they have multicultural content and are "down with the whole Japanese postmodern thing," and once he's in an institution then Chip and Muffy just have to have one. But his work is thin compared to the real thing.

On the high-low dichotomy, I said earlier the Japanese have no Romantic, starving-in-a-garret tradition, before reading in the Lubow article that Murakami famously sleeps on the floor of his studio. But hey, we all know some of the richest people in the world are some of the cheapest, bringing lunch to work in a brown bag, driving a beat up car, paying their employees nothing. That's how they got rich--by keeping their overhead down. In the Lubow piece a curator mentions the sleeping bag factoid, dutifully building the Zen monk artist hype around Murakami. Yet it's hard to square the image of this dude walking the earth like Caine in Kung Fu also licensing his designs for Vuitton handbags and going after a younger artist like Eric Doeringer who dares to appropriate his precious work. PT Barnum had a phrase that applies to many working in US art institutions.

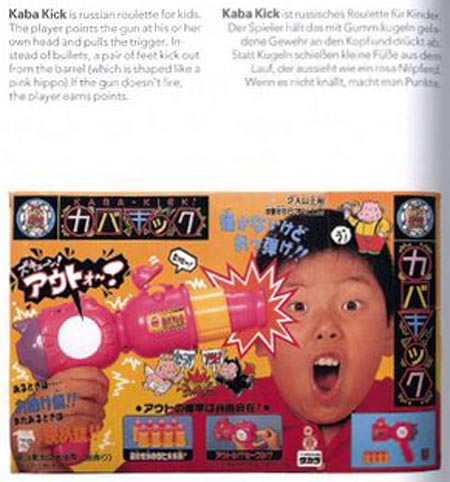

Top: Kaba Kick, a Japanese game of russian roulette for kids (I forget where I found this). If you lose, a pair of feet kicks out of the gun, which is shaped like a pink hippo. Artist Takashi Murakami, who has made himself a market force in the West selling to curators and art critics the easily-digestible idea that Japanese pop culture is about that nation's "impotence," would no doubt have a field day with this. In the interests of giving equal time to an opposing meme, the bottom image is Captain Goto, from the long-running TV adventure series Patlabor. "Patlabor" is short for "patrol labor"; a "labor" is an oversized robot that, in the near-future sci fi world of the series, is used primarily for construction work. Occasionally the stressed-out drivers of these powerful contraptions go berserk and the "mobile police" (also driving labors) have to be called in to restore order. The show somewhat resembles Taxi in being centered around a daily, humdrum work environment and follows a group of regular characters, the overworked, underpaid cops of Division Two, which Goto commands.

Goto's much like Humphrey Bogart in looks and demeanor--a supersmart, supercool guy who never lets on he's figured out a solution to a complex problem until time to put the plan into action. The show's juice is the contrast between his staff's daily bickering and the absolutely harrowing situations the job puts them in. Driving the monster robots is treated like a 9 to 5 gig but requires lightning reflexes, aggressive fighting skills, and a tolerance for hastily improvised solutions. As boss, Goto deals stoically with equipment shortages, departmental infighting, and short-fused subordinates and almost invariably thinks his way to a solution. In other words, the show has universal, positive appeal, and the "impotence" of Japanese society is the impotence of any other society (like, say, watching the slow motion train wreck of Bush's Iraq war and not being able to do a goddamn thing about it). It is uniquely Japanese in its focus on the "how-to" of the robots and the group energy devoted to their maintenance, and in showing how Division Two's sharp idiosyncratic personalities eventually reach consensus: even with Goto's guidance it is usually teamwork that wins the day.

This makes the series sound earnest but it is in fact fairly subtle in balancing the difficulties of life in a complex urban/industrial society with an upbeat story line. The cops have a knack for arriving late and operating in a state of crisis, but they do their jobs and mechanized society grinds on.