View current page

...more recent posts

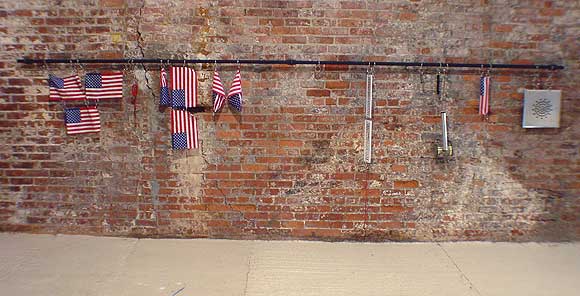

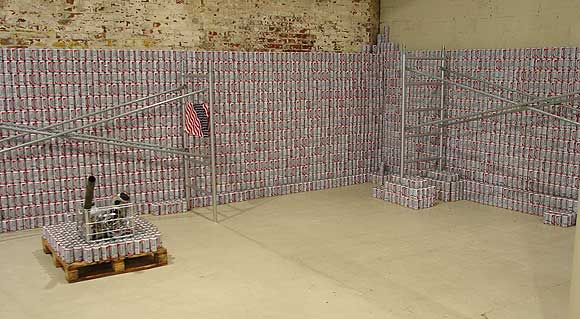

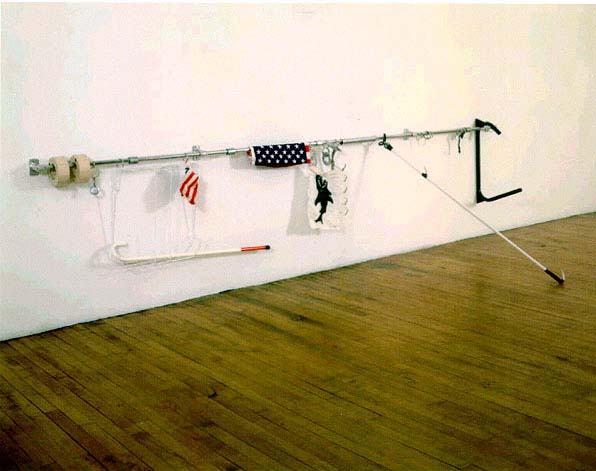

Not everything in Triple Candie's re-created Cady Noland show is so great--the strips of tape holding up the rather dog-eared Oozewald simulation are a poor substitute for thumbtacks (if that's what they originally were), and some of the fabrication looked amateurish, and not in a good way--but the above three pieces are superbly done, if superb is the right word. I took these photos yesterday--I actually saw something very close to the top two works (and met Noland) when she did a large-scale exhibition at the Dallas Museum of Art in '93, and can vouch that these versions are much like what I saw. Which is to say, offhand/slacker and fanatic/Judd/minimal at the same time. The main difference was--is this crucial?--no slick white gallery walls behind them, just Triple Candie's rough brickwork.

The show isn't just about creating a room of uncanny perfect copies, a la Sturtevant's Duchamps. It's also about whether recreating an art based on past ephemera is possible. And of course, whether the participation of the artist is essential in displaying work based on available materials. The artists have published detailed notes of how much or how little they were able to redo given their budget and the vagaries of finding (or re-finding) manufactured items from 20 years ago. They are completely up front in the press release that these pictures are based on, among other things, pictures on the Internet. In his hatchet job on the show, New York Times critic Ken Johnson doesn't mention that the Web was one of the sources used, thus writing out of history the rather important theme of how we rely on Google searches and cyber-facsimiles to give us our sense of history. It's quite possible that the photos above will show up in Google Images next to jpegs of actual Nolands. Is that good? Bad? Johnson doesn't go there.

An odd contradiction in Johnson's review: in the first paragraph he mentions that Triple Candie is a non-profit gallery, and then later says the show "might raise questions about art and commerce" (that is, if the gallerists didn't have such bad motives). He is projecting a set of intentions on them that differs from the ones they announced, and then slamming them for failing (or is it not failing?) to live up to them.

Just for the record, the re-creators are Taylor Davis, Rudy Shepherd and two anonymous artists. This post has been updated as new thoughts occur to me.

Update: Jerry Saltz also bashed the show. Typically, he describes many of the reasons it's interesting and then pronounces it shit. In this case, apparently based on loyalty to Noland and attachment to his memories of first encountering her work. He thinks she should sue the gallery--excuse me, "get a lawyer to get medieval on Triple Candie." He also passes along the insinuation that the gallerists are serially doing shows against artists' wishes, adding the unattributed anecdotal information (i.e., rumor) that David Hammons was "livid" about the show they did of his work. Not livid enough to stop the show in court, though. And is saying the artist didn't like the show the same as saying the gallerists "have gone around an artist's wishes," as Saltz does? As with Johnson, that's a nasty accusation to make without proof.

Update 2: This show is bringing out some conservative reactions in critics. Brian Sholis took the same protective line as Johnson. Like Saltz, he seems to think it threatens or cheapens Noland's legacy. But he hadn't seen the show when he wrote his post--he was reacting to the press release.

Update 3: As bill says, "Real or memorex?"

"Walker Evans Approximately'": Photographs, 1934 to 1956

Artists' Space

Through May 21

Recently artist Sherrie Levine mounted an unauthorized exhibit in the form of "rephotographed" works of photographer Edward Weston, using images taken from books, catalogs and magazines. Weston's estate threatened legal action.

For her next project, Ms. Levine has simulated a Walker Evans exhibition, copying a number of of Mr. Evans' haunting Appalachian realist photographs from the 1930s and '40s, using reproductions in books and magazines as guides. The works on view include the famous photo of a weathered couple on a porch ringed by scrawny urchins, and the curled, beat-up farmer's shoes that have been compared to Van Gogh's genre studies.

The show might be seen as a chance to think about an oeuvre that remains pertinent to what artists like Sally Mann, William Christenberry, and Sebastiao Salgado are doing these days. Unfortunately, it is easier to see it as an attention-seeking stunt. No one who values Mr. Evans' work is going to care about seeing inexact substitutes, and no serious critical judgments about his art should be based on such ersatz objects.

The show might raise interesting questions about art and commerce, but Ms. Levine should make it clear whether she is a photographer or doing her own conceptual art. Otherwise her project comes off as confused, confusing and duplicitous. KEN JOHNSON

That's not really a parody, it's almost word for word what New York Times critic Ken Johnson wrote about Triple Candie's Cady Noland show. Next up, another artist who needs to make it clear what he's doing: Richard Prince.

Ken Johnson of the New York Times yesterday criticized the gallery Triple Candie for its show of Cady Noland re-creations. His review appears to contain significant factual errors, based on what I learned from a call to the gallery. For example, was Cady Noland contacted about the show before they did it? The gallery says no. Johnson says she was, and that she "rebuffed" the gallery. Where did he get this information? Also, he says Triple Candie was similarly rebuffed by David Hammons about doing a show of his work before they went ahead and did it, also apparently not true. These facts are important because Johnson's review reads like a smear job on the gallerists, suggesting they do shows motivated by personal spite. Here's what the Times published:

"Cady Noland Approximately'": Sculptures & Editions, 1984 to 1999

Triple Candie

461 West 126th Street, Harlem

Through May 21

When the artist David Hammons recently rejected an invitation to do a show at the nonprofit exhibition space Triple Candie, the gallery's directors, Shelly Bancroft and Peter Nesbett, did one anyway. They mounted an unauthorized retrospective in the form of photocopies of Mr. Hammons's works taken from books, catalogs and magazines.

Now, similarly rebuffed by Cady Noland, the influential sculptor known for refusing to cooperate with commercial galleries, Ms. Bancroft and Mr. Nesbett have simulated a Cady Noland exhibition. They invited four artists — Taylor Davis, Rudy Shepherd and two who asked not to be named — to copy 11 of Ms. Noland's darkly acerbic Neo Pop constructions, assemblages and installations from the 1980's and 90's, using reproductions in books and magazines as guides. The works on view include an installation of Budweiser beer cases, steel scaffolding, auto parts and American flag bandannas; a cut-out and perforated figure of Lee Harvey Oswald being shot; and a wooden, silver-painted Minimalist sculpture of stocks, the old instrument of public punishment.

The show might be seen as a chance to think about an oeuvre that, while mostly inaccessible, remains pertinent to what young artists like Banks Violette, Josephine Meckseper and Kelley Walker are doing these days. Unfortunately, it is easier to see it as an attention-seeking stunt. No one who values Ms. Noland's work is going to care about seeing inexact substitutes, and no serious critical judgments about her art should be based on such ersatz objects.

The show might raise interesting questions about art and commerce, but Ms. Bancroft and Mr. Nesbett should make it clear whether they are running a gallery or doing their own conceptual art. Otherwise their project comes off as confused, confusing and duplicitous. KEN JOHNSON

An earlier post I did on Triple Candie's Noland show (more specifically, its intentions announced in the press release) is here. Johnson's review is scolding, judgmental, and apparently inaccurate. His theory that the gallery is motivated primarily by backbiting and "attention-getting" lets him off the hook from actually doing much thinking about the show. Possibly he has a bee in his bonnet about artists appropriating other artists' work. As noted here a year ago, when he reviewed Elaine Sturtevant's Duchamp re-creations at Perry Rubenstein he somewhat dismissively remarked, "They love her in Europe."

Update: This post was revised from its original form. I'm looking at the show this afternoon and hope to post more thoughts later.

Atrios, Juan Cole, and Steve Gilliard are all running ads on their blogs that say "Don't let the government regulate the Internet!" Those ads are paid for by AT&T and other telecommunications companies, using the alias of a fake grassroots group. It is regulation that assures "net neutrality" and creates a level playing field between independent content-providers (like this blog) and the big companies that brought you Fox News and Britney Spears. Ending regulation means no more level playing field.

Also, we've just found out these same TelCos who want to end the Internet as we know it have been selling our personal information to law enforcement agents.

It does seem like a disconnect that there could be a benign part of the government that regulates food and drugs and keeps competition alive in the marketplace and a malignant part of the government that spies on us.

I don't think that's much justification for taking the Telcos' money and helping them spread propaganda, though. It's a bit like the footage in Fahrenheit 9/11 of Al Gore banging the Senate president's gavel repeatedly, to keep the people who voted for him from speaking out about the fraud in the 2000 election he just "lost." Working against your own interests, as it were. Epecially since the issue is so confusing. Most people will assume that those bloggers want the government's "hands off the Internet."

"Acid Casualty" [mp3 removed]

Two of my favorite CDs are 808 State's Newbuild, which is acid house made when A Guy Called Gerald was still in the group and before they "got it down" and started producing club smashes, and the collection Acid Classics, on Trax records, which is all the best stuff from Chicago in 1986-88. I love the intensity of the music and also the "I made it at home" quality. Tried to do something in that spirit here (although the synth used in the "break" is a bit more '92 hardcore rave.) No one can accuse me of being nostalgic for acid house because I had no idea it existed in '88--at least not the wack form you hear on Newbuild. I was on board by the early '90s, but by then the music had already mutated into something else. Interesting to think back to pre-Internet days--how slowly it took scenes to find their way to their potentially most enthusiastic audiences.

Tristero at Hullabaloo has dinner with a "liberal hawk":

"No, no, let me ask you a question. How come you, a musician, maybe a good one, maybe a well-read one, but a musician with no training in affairs of state - how come you of all people were right about Iraq but the most respected, most experienced, most intelligent, most serious thinkers in the United States got it wrong?"We have a liberal hawk who used to post a fair amount here at Digital Media Tree, and I had some lively debates with him during that period when America was going off a cliff. Unlike tristero's hawk, he didn't question my credentials to question the war, but he did a lot of scaremongering. "What if Saddam nuked the Saudi oil fields?" "Saddam or Osama (I forget which boogeyman) wants to establish a New Caliphate and rule the Middle East!" (Or words to that effect.) What it came down to was he believed ex-CIA analyst Kenneth Pollack about Iraq, and I believed ex-UN weapons inspector Scott Ritter, who had been in the country and said it had no weapons of mass destruction. Also, unlike tristero's defensive hawk, the Tree's hawk doesn't continue to defend his judgment. He's just been very quiet the past couple of years. It's a shame--he's a bright, knowledgeable guy and I miss our debates.

"That is a question I ask myself every day, because it scares the daylights out of me," I replied.

My eyes started to tear up and the winter of 02/03 raced through my head. That awful sense of dissociation watching every American media outlet try to outdo its rivals by printing lies, the unspeakable dread as I watched my country willingly go over the abyss. The shock of realizing that nearly everyone I knew had bought the myth of the Good War and that nothing I could say or do, nothing anyone could say or do could change their mind. It was too late.

I tried to say more, but I couldn't, and then the subject changed and the dinner went on.

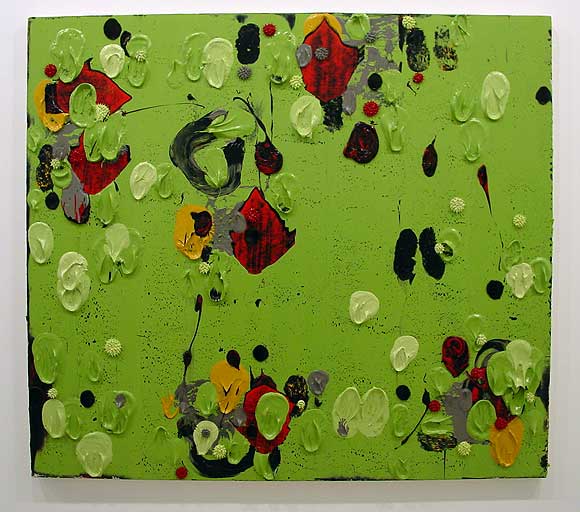

Just got back from Dennis Hollingsworth's opening at Nicole Klagsbrun in Chelsea, where I took this pic of one of Hollingsworth's paintings, and met the artist for the first time. Nice guy, but I knew that from his blog (still a comparative rarity--a generous walk around his life and studio). The photo makes the piece look small, but this is about 4-5 (?) feet wide. I like Dennis's work and have enjoyed watching it evolve on the Web. Nothing like seeing the real thing, though. I think you can get from the photo how sumptuous it is. What you don't get is the complex interplay of layers, and the gritty, gestural quality that invokes Pollock as well as taggers. These aren't facile paintings, you sense a lot gets scraped off before they start working. Earlier posts on Hollingsworth are here and here.

Digital Non-Sites

A few years ago I was in a show in Washington DC called "Digital Sites," which featured artists from the gallery side of things who use the computer in their practice (Albert Oehlen, Matt Mullican, Wayne Gonzales, Marsha Cottrell, etc.)

Response from the art world was flat, as these things usually are--minimal sales as far as I know, a couple of sniping or dismissive reviews. In 1999 I did not yet realize the depth of the "computers do not belong in the art world" conspiracy and couldn't have foreseen that painting would tighten its grip on the market to the extent it has. I mean, I like Dana Schutz's work, but it's just recycled German Expressionism, yet collectors are treating it like spun platinum.

The title "Digital Sites" was good, riffing on the dual meaning of the term "sites"--as in web sites, but also site specificity. The latter had its roots in the practice of earthworks artist Robert Smithson, who also came up with the term "Non-Sites," which are physical pieces, such as minerals from a quarry hauled into the gallery and displayed in a metal container.

Lately in my work, including the solo show that's up now, I've been experimenting with the idea of "Digital Non-Sites." In other words, content that lives and thrives on the Internet, such as animated GIFs, that has a second, qualitatively different life in the gallery. This could either be video or drawings of individual animation frames I've been posting.

That's the theoretical hook anyway. *crickets*