View current page

...more recent posts

"Hey" [mp3 removed]

The sample of a guy saying "Hey!" was snipped from a song on the Grime Time website. Most of the percussion is apparently echolocation sounds made by bats, from a Native Instruments Battery kit crafted by Plaid. So, lots of vocals here--a first. The rest of it is semi-familiar club stabs.

Haven't read all of this Vanity Fair article yet, but apparently the gist of it is that the 9/11 hijackers did have help from the US government--not in the form of a conspiratorial green light but a Keystone Kops leadership vacuum. According to a "complete" set of tapes listened to by the VF reporter, the air defense agency NORAD was scrambling jets late, and to the wrong places, as it followed up on rumors of 10 possible hijackings the morning of 9/11. By 9/12 it had 300 jets aloft over various US cities but when its efforts mattered most, all the hijackers slipped through our air defenses.

Fortunately, Americans knew that the biggest problem of 9/11 was not a "worldwide terrorist network based in Afghanistan" but our own government's incompetence in the face of a spectacular, tragic one-off incident. The people rose up as one, and pressured Congress to impeach Bush and "shut down the government" through the power of the purse, until more competent leadership could be put in key Executive Branch positions. A triumph for our democratic system: It would have been doubly tragic if the US had gone off half cocked and invaded sovereign nations, weakening our military even further.

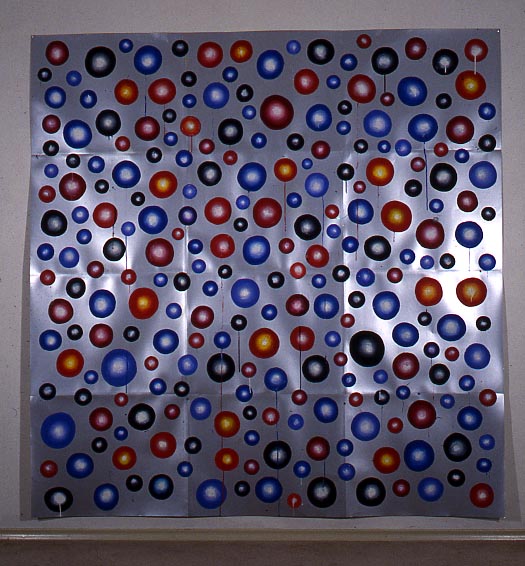

Psychic Highway, 1994, gouache on aluminum-coated paper, linen tape [along seams on back], 81" x 78" (destroyed 2002)

Getting the water-based gouache paints to stick on that metallic surface was the challenge of a lifetime. By 2002 so much had cracked off it the piece had to go to the landfill. The drips are all fake--to give the look of zestful spontaneity. A bit Scharfish but without his commitment to creating a fine, permanent object.

Dennis Hollingsworth's paintings have been mentioned here a few times. What follows is an attempt to describe the work and answer some criticisms of it.

Let's start by saying what it definitely isn't:

"just about paint"

That's like saying that The Rite of Spring is just about musical notes. If you think the canvases are some dull, said-a-million-times statement about materiality, as some commenters have suggested, please look again and remember that the whorls, blobs, and explosions are not mere accidents but also a record of events shaped by a human consciousness. Not a vision of an animate cosmos as literal as, say, Blake's, but still a teeming universe of suggestive contours and textures, thwarting powers of speech--a morphed mashup of animals, ghosts, genetic mutations, war wounds, and impossibly tangled plant life, at least in this viewer's art-prompted reckoning.

One could say in '80s jargon that his thick paint is a hyperrealized version of past expressionist art--a Baudrillard term meaning roughly "on steroids." But to call it pornographic, as one commenter did, rather ignores the joyful, non-synthetic element. The artist says the work is an "affirmation of paint" after the negation of the post-Modern years. But does that make it Modernist? If so, it's closer to surreal, abject side of Modernism that Clement Greenberg and other 20th Century critics tried to edit out of history. The colors may be joyful, but the sea urchin-like blobs that cling to everything seem vaguely alien and parasitic. The intricate cutting and slicing of organic forms suggests an anatomist's inner burrowing.

And lastly you have the linguistic side of Hollingsworth's work--a hermetic system of recurring elements (which have names--see Scott Speh's review) that serve as a private lexicon in a state of perpetual breakdown and reshuffling. This recombinant practice hews closer to postmodernism than the Modernism that forever proclaimed its abstract vocabularies as new and scientifically derived. Hollingsworth's work is aware of nonrepresentational conventions and builds on the limited vocabularies of Peter Halley, Jonathan Lasker, et al, who in turn built on the Abstract Expressionists. Yet ultimately his fearlessness to engage in actual, dense, convoluted, expressionistic (or expression-like) paint handling gives him a richer and more varied range of iconography than those predecessor "deconstructors."

Update: Revised in Feb. 2009.

Gro-Rabbit--artist and actual title unknown

Talking about art conservation issues makes me miserable. It's soul-deadening and antithetical to art.

Dennis Hollingsworth has posted a thoughtful reply to my post about a recent painting of his. He also responds to some of the comments about his work after that post, which ranged from complimentary to dismissive to WTFBBQ? To answer queries about the physical creation of his paintings, he offers an annotated photo of his studio tools. These reminded me of an interesting exhibit a few years ago at Apex Art in NYC, curated by Charles Goldman, called "Making the Making," where Goldman presented an array of the actual home-built devices used by artists to make their work. The variety of people's creative methods, as reflected in the eccentric and/or scrupulously precise objects on display, suggested an alternative form of discourse, approaching the level of art itself. It's an esoteric subject, but unlike, say, the museological presentation of writer's notes or musical notation, or even the how-tos of movie F/X, visual artists make this behind-the-scenes stuff so there's a higher chance it will have intrinsic visual interest, or even a reflexive function. Hollingsworth's "daubers" of wrapped, stained cloth, and the origami pincers he uses to create his sea-urchin-like "monads" might have been a nice addition to Goldman's show.