View current page

...more recent posts

My print criticism continues to surface on the Web like submerged bodies rising in a Meadowlands pond. Here's my Artforum review of Randy Wray's 1996 Kagan Martos exhibition. I enjoyed looking at Wray's website, about which more later. Missed the last couple of shows, unfortunately, but in the paintings I've seen, the tension between abrupt bursts of ideas and obsessive time-filling noodling within the same piece is compelling. It's tempting to say they're Seinfeldian in that no subject becomes the subject. I still think I prefer the earlier, punchier works, but it's fascinating watching his thought process...mature? deepen? not sure yet (you, too, can follow this development by paging though the slightly-too-small but kilobyte-intensive website pics). He does use the computer now for developing ideas, but too much could be made of that--they're still about painting, sculpting, drawing, and paint-by-number handicrafts. You don't feel much "cyber" in the work--it could just as easily be elaborate Polke-esque stencilling.

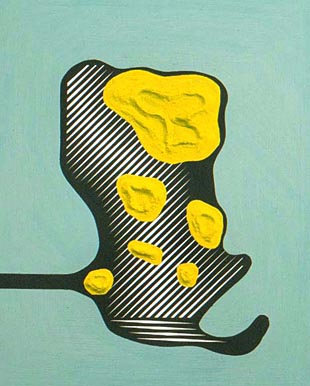

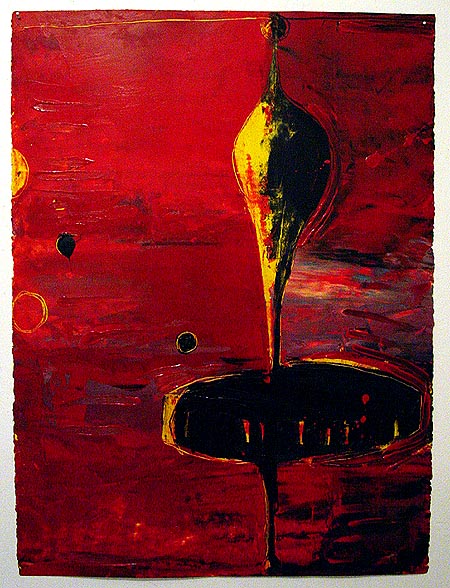

Old scores: this piece, Nest, was the image I wanted to accompany my Artforum review, instead of the one they ran (it was the dealers' fault for sending in something else). This would have popped off the page in AF's black and white postage stamp format.

Trax Records, the seminal Chicago house music label, just re-released some vintage recordings, and the Seattle Weekly's review of them is worth a read. I just purchased Acid Classics and my jaw elevatored down to hear this music I completely missed when it came out in '86 (!) through 1990. (I knew about House but had no reliable way to get my hands on the vinyl.) By now we've heard these moves a million times--the trancy squiggle of the Roland TB-303 is a musical institution--but these early, stripped-down psychedelic funk engines still sound radical. "Acid" is the most techno-y side of house, and the beats are as minimal as it gets, but still seductive and completely up to date. There's simply no comparison between this music and the "industrial" style of pre-techno that was appearing around the same time--Front 242, Nitzer Ebb, Single Gun Theory--whose beats were much more pounding, metallic, obvious, and, now, dated. (Although I still have a soft spot for Nitzer Ebb.) Laurent X's "Machines" and Adonis' "Two the Max" are brilliant.

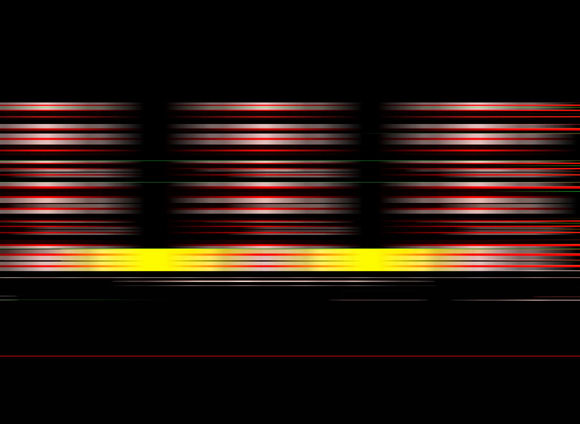

In a comment to the previous post, Brent questions whether Chris Ashley's stationary HTML drawing and jimpunk's moving .GIF are comparable or compatible on the same page. My usual quip about showing video next to paintings in a gallery setting is that it's like bringing a baby to a wedding, but the browser is the great equalizer. A few more line breaks were added to the post so the pieces aren't quite so close together, but otherwise, yeah, I think they have more in common than not as art non-objects. Although neither artist is an Op artist in the old '60s sense, the pieces exploit optical tricks over and above their plain formal appeal: illusory depth in the Ashley and quite literal vibration in the jp. Moreover, they are fresh takes on the grid and opticality, which the New York Times and the Village Voice love to dismiss as the concerns of a bygone generation, in spite of all evidence to the contrary (e.g., the Infinite Fill show.)

Chris Ashley - Untitled (Blue and Green) 18, 2004, HTML, 320 x 240 pixels:

jimpunk, ( [ ] ), 2004 animated .GIF and HTML:

|

Re-reBlogging a couple of items from yesterday. More commentary will eventually be added, perhaps when I return to decelerated blogging life a few days hence. Ashley's drawing is straight-up HTML, and jimpunk's piece uses HTML to vertically stretch this gif (

UPDATE: This "website bricabrac" is some Apple "loading--please wait" icon thingy that's been turned from pale blue to black and white. I'm surprised no one told me I was revealing my Apple-ignorance (again).

Official website

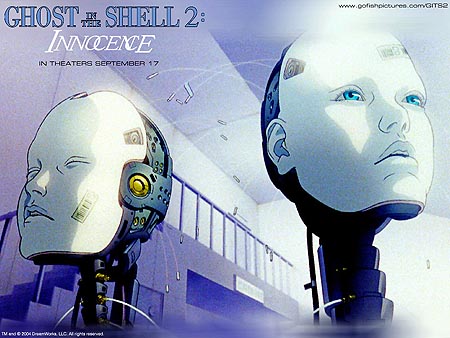

Spoiler-ridden interview with director Mamoru Oshii:

From the trailer it looks like a lot of CGI machinery awkwardly mixed in with character drawing. The story idea seems lifted straight from Armitage III, only with more of that heavy out-of-body stuff (and melancholy) that is Oshii's specialty. I mean, the man didn't look the interviewer in the eye once! (Thanks to del.icio.us/moth23 for the link).The original Ghost in the Shell, adapted from a manga (Japanese novel in comic-book form) by Shirow Masamune, inspired Andy and Larry Wachowski to make The Matrix [what didn't? --TM] and topped stateside video sales in 1996. Innocence, which premiered at Cannes last spring, catches up with Batou, a cyborg detective who journeys through a futuristic cityscape to crack the case of the killer gynoids (a term coined by Oshii). The prostitute ring of robotic Geisha-like sex-toys turns out to be masterminded by Kim, a crafty doll who fends off the investigation by implanting false experiences into Batou's "e-brain."

The sleuth eventually reunites with the Major, who exited her "shell" to become pure soul -- a ghost -- at the end of the first installment. Together they rescue hapless gynoids who become animated by having the ghosts of real girls "dubbed" into their bisque-coated physiques. In between his battles with Yakuza thugs, toxic firewalls and homicidally programmed assassins, Batou, Oshii's self-proclaimed alter ego, discusses Descartes, quotes Shelley and cites biblical passages.

UPDATE: Saw this on Sept. 21. It's beautiful to look at, like Peter Greenaway's Prospero's Books, which I also fell asleep in. Really don't like the combination of CGI (with obvious photoshop textures) and cartoon anime.

Above: John Pomara, oil on paper, ca. 1987. Speaking of painters braving the switch to 1s and 0s, the piece above is what Pomara was doing in '86 and '87 (gorgeously painted semi-abstractions with roots in AbEx, the east village, and '60s sci fi book covers) and below is a detail of a recent piece:

Pomara starts with a pixelated blow up detail of an image such as a face and gets busy crunching in an imaging program, refining and deforming and refining until something that looks like modernist architecture emerges. He does still paint, and these images are used as stencils in that process and also printed out as stand-alone photo-works. I maintain that a painterly eye transcends media and we're too fixated on the physical stuff: obviously output is important, and that's something we're all wrestling with. I'm confident that solutions will continue to be found that will save us from the dreaded fate of becoming printmakers. Calling the output "photography" is one conceptual end-run around the problem.

Diana Kingsley, Court Disaster, 2000-04, still from 2.5 min. loop, DVD on video monitor

New York artist Diana Kingsley, who I've I've written about a few times, just concluded a show at Leo Castelli, after earlier appearances at Derek Eller and Bellwether. The New Yorker reviewed it during its July/August run, and this week, Artnet observes: "With its visual reductiveness, Kingsley's work has the starkness of pulp fiction, where bare facts and descriptions set a mood more than they add up to a story. Her video narratives are tenuous, threatening to wink out and leave us with still imagery." To which I would add that the videos, like her still imagery, seem calm and innocuous at first but each contains some hint of the ominous, a mini-disaster waiting to happen.