View current page

...more recent posts

|  |

|  |

|  |

|  |

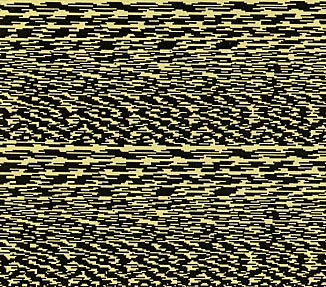

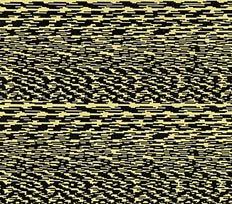

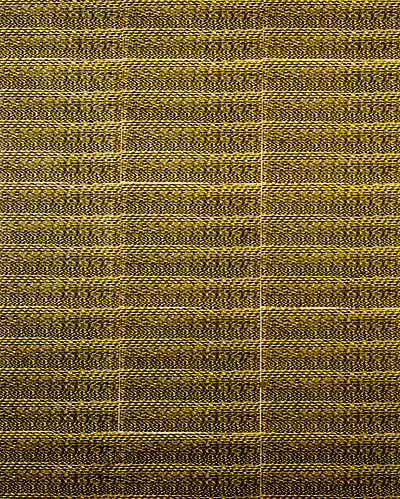

When I sent a drawing from the MSPaintbrush program on my computer to the network printer, the printer routinely sent back a message announcing that the job was finished. This caused a slight power surge, and I discovered that if I was sending another drawing to the printer at the exact same moment, the signals would cross and the second image would get "zapped," printing out as a uniquely garbled geometric pattern. I actually learned to time to the split-second when to send the drawing to get a good "scramble."

I made multiple photocopies of the scramble-pattern and joined them in a grid, applying linen tape to the back of the paper and then folding the paper around a painting stretcher and stapling it on the back. The result is a rather elegant, minimal quasi-painting born out of the drudgery of the modern office (during periods of official "down time," of course). The differences in color in these web pictures are just discrepancies among the scanner, slide, and digicam images used to make them.

I started thinking about this work again after the recent interview where jenghizkhan said "I started making music by scratching CD's [as in hiphop, turntable scratching] that I made from digital noise samples (similar to modem tones). I got the samples from saving the screwed up files that my computer sequencer would spew out when it crashed (which was all the time in the beginning). The scratching occurs sometimes at a super subtle and slow rate so that I can draw out all the tones that make up the white noise of digital streaming information."

That got me thinking about visual equivalents to those kinds of sounds, and the interest that exists across disciplinary lines in digital by-products, especially down at the "molecular level."

I purchased jenghizkhan's SidStation synth, as we discussed in our interview a few posts back, and got it hooked up a couple of nights ago. Here's a preliminary report. First, it remains to be seen whether this quote from Walker Evans, which I found on Bill Schwarz's page, will be relevant:

Time and again a man will stand before a hardware store window eyeing the tools arrayed behind the glass; his mouth will water; he will go in and hand over $2.65 for a perfectly beautiful special kind of polished wrench; and probably he will never, never use it for anything.The SidStation is a beautiful thing, in its simple and modest design, but I mean to use and not just drool over it. It's a bit like programming a cell phone, in that you punch arrow keys to move around within menus on the little green LCD screen. To make sound, you're supposed to control it with something. Most people would use a keyboard but I hate keyboards because I associate them with the past trauma of sixth grade piano lessons, so my goal is to use notes that I plug into a musical staff on my downloaded notation program (called Harmony Assistant, or HA).

Wednesday night I successfully got the SS hooked up to speakers and got the MIDI cables hooked up so my computer sends notes to the SS to play. Harmony Assistant appears to only send one MIDI channel to an outside instrument--I haven't figured out yet how to make it control more than one. I had hoped to be able to use the SS as a "lead instrument" in connection with HA rhythm and bass lines playing off the sound card in my computer, but with the SS hooked up to the speakers, I can't hear the other staves playing in HA. I'm going to try running lines out from both the computer and the SS to my mixer, so I can hear and record both sources.

The SS is built around an actual, vintage Commodore sound chip from the '80s so it's limited in certain ways. It only produces sawtooth, square, and triangle waves--there are no smooth mellifluous sine tones, and everything sounds scratchy and buzzy and, well, like an old computer. jenghizkhan thoughtfully loaded the SS with preset "patches" from the SS website, which I haven't yet learned to modify, so I may still find a way to make a smooth sound. Some of the patches are single notes but most are loops of a handful of notes, so when you press an "A" note you hear a broken chord or prerecorded melody beginning with that note, "B" gets you the same sequence beginning with "B," etc. I want to start off working with single note melodies that I write (after first modifying the texture of the notes), so I already know there are lot of patches I won't be touching for a while. I clicked through all 90 or so patches and listened to them, using the real time editing knobs just below the green screen to alter them, and heard many cool sounds (and some obnoxious ones). I'm acclimated to my ancient Macintosh's array of lo-fi sounds so this still feels like an alien environment.

I just got some work photographed by Bill Orcutt, a pro who's taken my documentation shots for several years. Now I have transparencies made with a large format camera, with nice even lighting. After resizing for the web, they're still fuzzier than I'd like. A first stab is here, saved at approximately 270 KB. I may go a bit larger in the quest for more detail.

In a comment to a previous post Brian writes:

Interesting you would say, "That show was...critically successful...but the work isn't collector friendly because it's huge, aggressive and made of photocopy paper (precisely the things that make it appealing to critics). I've put a lot of thought and effort into resolving this contradiction." This sounds a bit like the tail wagging the dog, no? One of the things I've enjoyed about your work was that it always appears to be undeniably your work, operating in your sphere unaffected by the rumblings from without. Please tell me this is still the case.My reply: Yeah, I know it sounds like I'm selling out but the institutional frame (as in context) is important. Those big paper pieces appeared in a gallery and were seen because someone thought they could sell them. That's how the system works here in the USA. That validation process gives them an edge, which has always been in my work--a "good bad" painting doesn't really work its magic till you put it in the white cube. The physical framing of my current pieces does something similar: it says somebody thought enough of this computer-, home printer-made thing to plunk down the dough for museum-quality presentation of it. Now it looks like it's in the stream of commerce--something that could travel around to art fairs and be seen and discussed like the other stuff that travels around to art fairs and gets seen and discussed. I think it's better to acknowledge and confront the medium of exchange than adopt the pose of the heroic outsider. The work is just as subversive, trust me.

It's also not really selling out because of the second-tier status of paper. A painter friend said, "You've got to figure out a way to get this imagery printed on canvas, man. Then you could sell them!"

Claire Corey and I will be speaking at dorkbot-nyc ("people doing strange things with electricity") on Wednesday, November 3. Matt Hall and John Watkinson are also on the program. It's the day after election day and the mood is either going to be upbeat, or...well, you know. I'll be posting notes as the event approaches, but I like this phrasing of Claire's, describing her practice as a digital painter: "This hybrid medium questions both what is expected from works made with a computer as well as what constitutes painting." I've been thinking something along those lines in connection Jason Salavon's "100,000 Abstract Paintings," AKA Golem, where he wrote a software program that encoded parameters (size of brushstroke, color, etc) but also painterly qualities derived from studying the moves of Diebenkorn, Richter, and others. There is a dual critique there. What do we expect the computer to be able to do for us? Assemble cars? Play chess? Paint? Which tasks are necessarily "automatable" and which shouldn't be delegated? But also, what are attributes constituting "good painting" these days? If they're so quantifiable a machine can recreate them, are they really "good"? The critique is more obvious and pointed if you're talking about actually writing a program that does this (and I've seen Salavon's paintings and they're actually pretty "good") but it also applies to those of us just using the machine to make paintings: Claire, me, Millree Hughes... A curated show setting out these issues would be enormously helpful.

Gero von Randow made a mini-version of my "Centrifuge (Side View)" .GIF. A bit large, memorywise (188KB--the original is only 42KB) but very cute.

I posted the original here and on my Animation Log.

Thanks also to Three River Tech Review for linking to it.

Daniel Albright, a teacher of mine at UVa who is now at Harvard, returns often to the theme of "elementary particles" in poetry, music, and art--the charged, irreducible core memes that make art art. His writing has much to say to current digital practice, I think, where pixels, vectors, and 1s and 0s have become a philosophical as well as technological obsession. Quantum Poetics: Yeats, Pound, Eliot, and the Science of Modernism mercifully sidesteps New Age-y Tao of Physics murk in favor of single-minded focus on the wave/particle duality, dividing the poets into one or the other function. Thus, Yeats surfed The Wave with the all-encompassing poetic cosmology of A Vision, the image- and vortex-seeking Pound was a particle man, and Eliot's perverse blend of urban anomie and squishy undersea metaphors seemed All Wave until the appearance of "Christ particles" in his late work. Untwisting the Serpent: Modernism in Music, Literature, and the Other Arts begins with a consideration of the Laoco÷n problem--Lessing's formulation of the "rules" for expressing ideas in different media--and then zeroes in on peak moments in musical theatre where sounds, speech, and scenery achieve a synaesthetic unity. Albright takes most of his examples from the early 20th Century and avoids recent artforms based on newfangled gadgets, but many concerns of the Modernists--the interest in science, the exploration of psyches shaped by a technological society, the centrifugal splitting of aesthetics--have never been more relevant. (Which is not to say we have to throw out poMo critiques of those agendas.) Fair warning and/or full disclosure: In this blog and future writings I'll be leaning heavily on my old Prof's work as I stumble around trying to make sense of what's going on with new media, electronic music and tech-based gallery art.

Deborah Solomon's cutesy but miserable slam-interviews in the New York Times Magazine always take a little something out of your day. This week she talks to inept ex-CIA analyst Kenneth Pollack, who has a book out. In the runup to the Iraq debacle the debates on the liberal side came down to whether one believed former UN inspector Scott Ritter that Iraq had no WMDs, or Pollack's scare stories that Saddie the Baddie was going to nuke the Saudi oil fields and launch Armageddon. Here's Pollack now, sounding kind of flip about being so wrong (assuming it's not Solomon jiggering the quotes):

In your new book, ''The Persian Puzzle: The Conflict Between Iran and America,'' you seem to have abandoned your hawkish stance. Your last one, ''The Threatening Storm,'' helped persuade many reluctant Democratic policy makers to support the invasion of Iraq.Sorry really isn't good enough here, Ken. Instead of doing your book tour, why don't you spend some time in Iraq, say, helping medics sew kids' arms back on?

I made a mistake based on faulty intelligence. Of course, I feel guilty about it. I feel awful.

It's nice to hear at least one American say that he's sorry.

I'm sorry; I'm sorry!