View current page

...more recent posts

"Godhopper" [mp3 removed]

"Looplament" [mp3 removed]

From now on all my song titles are going to be three-syllable neologisms. Nah, it's just a coincidence that these two ended up with the Burgess/Huxley/Womack style newspeak. "Godhopper" is sort of a private joke, I think maybe two people over at FMU and/or some old prog heads will get it. I'm chafing over whether to make it more elaborate and satisfy the lust for nerdy solo-ing it seems to imply or just leave it. "Looplament" is a bit different from what I've been doing: it's slow, meditative and dorky, as opposed to fast, intricate and dorky.

"Suite 6 (E-Piano)" [mp3 removed]

One of the Sid songs rescored for synth and two electric pianos. A Latinate riff makes it fairly buoyant while the Rhodes moves it closer to Soft Machine Six territory. (Did I say I love Soft Machine Six?)

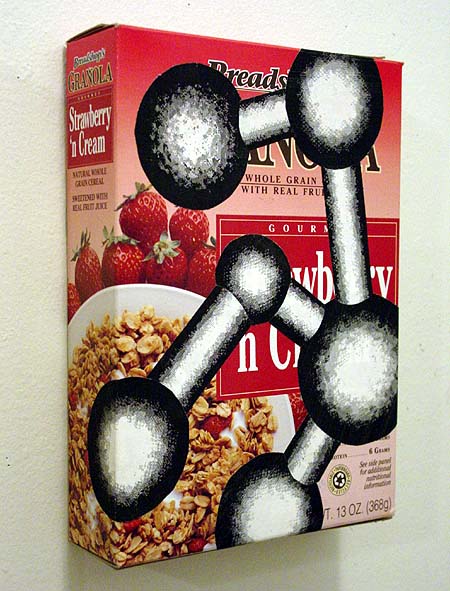

Drawing by Roy Stanfield, from a series based on random picks from Google Images. I think that's the way to go with this otherwise obsolescent skill called "drawing," so much slobbered over by art buyers. Thanks to all those search engine bots we're drowning in each other's image-effluent. Hand-rendering these pictures "personalizes" the sludge-flow while inexorably adding to it. Art is not an act of resistance but participation in a vast system of fascination and voyeurism. Signed, Baudrillard Junior. (Having said all that, I like this drawing--Steve Mumford should look and learn to see how the "courtroom style" can be used effectively.)

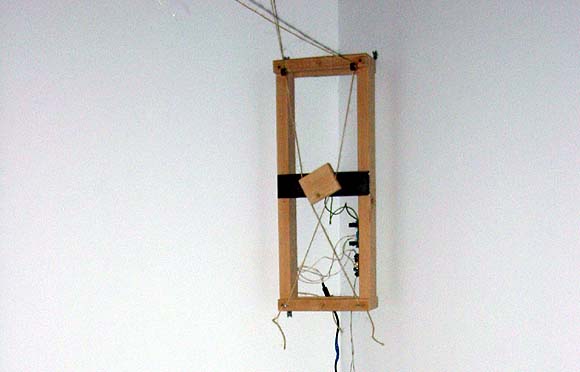

The clunky, slowly rotating cams (as in camshaft, not webcams) in Douglas Repetto's just-ended installation at Location One reminded me of this piece by Francis Picabia, consisting of cardboard and string stretched loosely in a picture frame (sorry I don't know the work well enough to tell you what's written on the cardboard). In my copy of Brian Wallis' Art After Modernism, the Picabia serves as an illustration for Benjamin Buchloh's famous essay "Figures of Authority, Ciphers of Regression."

It's arranged on the page in a before and after demonstration, with a later painting of Picabia's showing the artist posing with two beautiful women. The point supposedly being that Picabia was part of a wave of avant gardists from the 1910s who regressed to classical or conservative painting styles later in the 20th century. I always found it a hoot that Buchloh (or Wallis) thought Picabia's late work reinforced the status quo. What, bigamy? (Yeah, I know, fantasies of male over-empowerment, yadda yadda.) The man was never more out of favor with the art world than when he was painting nudie images out of French erotic magazines--those canvases didn't really become market-viable until relatively recently, after David Salle said "Hey, these are good!" There are inherent problems when a critic with absolutely no sense of humor uses an arch-ironist like Picabia to exemplify anything. Yes, Picabia wrote about the "return to order" in the '20s, but we should be talking about his art, not his spin du jour.

It's arranged on the page in a before and after demonstration, with a later painting of Picabia's showing the artist posing with two beautiful women. The point supposedly being that Picabia was part of a wave of avant gardists from the 1910s who regressed to classical or conservative painting styles later in the 20th century. I always found it a hoot that Buchloh (or Wallis) thought Picabia's late work reinforced the status quo. What, bigamy? (Yeah, I know, fantasies of male over-empowerment, yadda yadda.) The man was never more out of favor with the art world than when he was painting nudie images out of French erotic magazines--those canvases didn't really become market-viable until relatively recently, after David Salle said "Hey, these are good!" There are inherent problems when a critic with absolutely no sense of humor uses an arch-ironist like Picabia to exemplify anything. Yes, Picabia wrote about the "return to order" in the '20s, but we should be talking about his art, not his spin du jour."Slow Hooterville" [mp3 removed]

For Sidstation and analog drum synthesizer; additional percussion: Linplug RMIV.

A few months back I asked some questions* about how "tracker music" differed from early breakbeat hardcore and sequencer-based music generally, and I've still been somewhat confused. This post by Marius Watz, which Marisa Olson recently reblogged on Rhizome**, helped me quite a bit.

The arcane art of tracking takes what I like to think of as a hackerís approach to making music. The interface is primarily numeric, notes are entered via the keyboard, length, parameters, effects are often entered in hexadecimal notation, and code flies across the screen as if you were looking at the opening credits of The Matrix. Whatís not to like?*My questions from last April were: "I'm still curious (and googling) about the interrelationship of the Atari demoscene, amigatrackers, and early rave and 'ardkore. How much was hobbyist/cultist vs real club/dancefloor breakthroughs? Also how much was actually hacked and/or open source vs just using the products companies were selling? Then or now? From the wiki article it sounds like the Akai and the tracker software were inseparable 50/50 partners in defining the 'tracker' sound. Is that the same thing as 'classic' breakbeat rave or breakbeat techno? The article makes 'tracker' music sound like a cheesy variant--did that happen later or was tracker music always the music of hobbyists/Atari cultists? Finally, is the 'tracker scene' mainly a European thing?"

Kuro5hin has a good article and how-to on cutting up breakbeats with tracking. It lists possible software (such as Renoise) and gives a step-by-step breakdown of how to go about murdering the Amen Break (the biggest drumíníbass break of all timeÖ) For more insights into the origin of tracking culture, Salon.com has an article [from 1999 -ed] called MOD Love.

The Salon.com article points out that the analogy that tracking is to music what code is to software is a bit of an overstatement. Tracking, which involves writing notes and effects in hexadecimal code, is still much like sequencing. Its true significance seems to stem from the fact that tracking started as a DIY culture, by kids who had no access to professional equipment (and frequently, no musical training). But tracking also allows a mechanical approach to music that makes it attractive to practitioners of drumíníbass, breakcore, digital hardcore or plain old noise.

I've concluded that the scenes were completely separate in the late 80s/early 90s: tracking was the domain of hackers making mostly chiptunes or cheesy rave tracks, while Rob Playford, A Guy Called Gerald and other mainstays of early breakbeat and jungle were using primordial versions of programs like Logic, hardware sequencers, and more pricy (?) samplers. What's happened in the last few years is a late merger of the two styles, with trackers being used to trigger samples in very fast "jungle-like" music. In the earlier thread we had some miscommunication but I think I'm clear on this now.

**Update, 2011: The Rhizome link has been changed to http://rhizome.org/editorial/2005/nov/26/the-arcane-art-of-tracking-vs-the-amen-break/

My photos from Douglas Irving Repetto's show at Location One, 26 Greene St., NYC; the exhibit will be open one more day (tomorrow, Saturday, November 26). Microphones at the bases of mylar cones pick up room sounds, which trigger sensors causing the wooden cams to turn, making twine move on pulleys stretched across the room (think Fred Sandback meets Cronenberg's Spider), which in turn jiggle vertical sheets of mylar, making abstract reflections on the wall shimmer ever so slightly. As the press release describes it, "the piece 'breathes' in sympathy with the ambient sounds in the gallery, rippling and reflecting light when there is a sound and resting, invisible, when there is silence. Because of the transparency of the mylar strips, the effect is subtle and eerie, a gossamer membrane that functions as acoustic barometer, making visible sonic phenomena that are often heard, but rarely seen." The effect is not as dramatic as we're used to in this age of pyrotechnic insanitaria, but I believe that's the point.

Repetto's site documenting the piece is here.